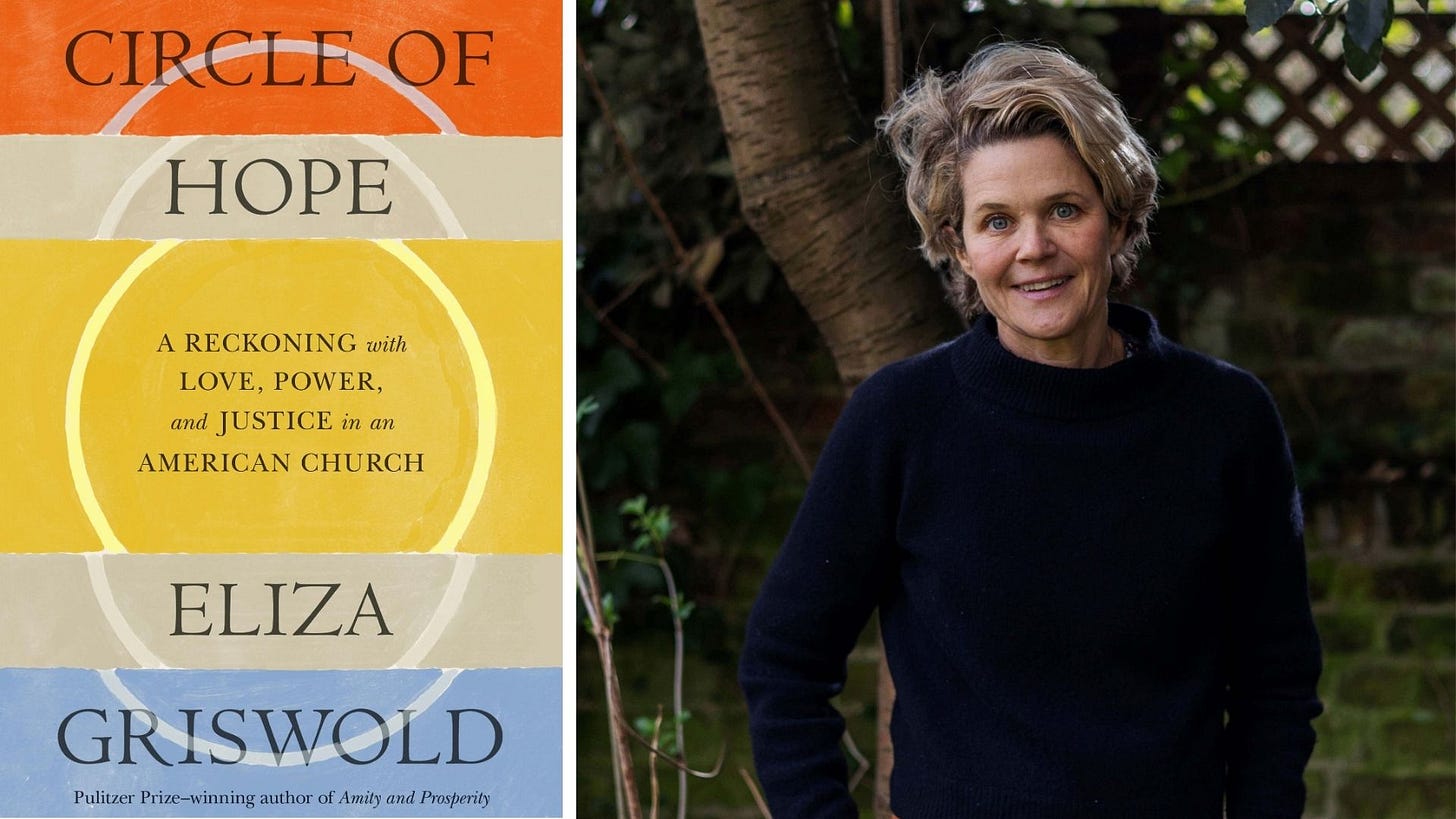

Eliza Griswold's new book Circle of Hope: A Reckoning with Love, Power, and Justice in an American Church is about a church in Philadelphia that was started by a couple who became dramatic converts to Christianity in the 1970's. They became Jesus people.

And unlike many others in that movement, they stayed pretty radical. Griswold's book tells the story of this couple's attempt to hand the church off to the next generation. It doesn’t go well. (You can listen to my interview with Griswold in the media player above, and on any major podcast platform, at The Long Game podcast.)

A hallmark of the Jesus movement was a simple faith practice that sought to live out the teachings of Jesus. Much of this was in communal form. For a brief moment in time, many young Americans were so high on Jesus that they made efforts of varying duration and scope to create communities of common life and intense religious practice, all the way down to sometimes sharing material goods.

But of course many of these young people got married, had kids, bought homes, acquired wealth (or didn't), and generally submitted to the weight of conventionality, which is a normal human pattern. The Republican party won over most of them with appeals to traditional family values and opposition to abortion.

Yet I have felt some disappointment that so few remained radical, a bit complacent and consumerist. But what if the story of those who remained radicals also turned out badly? That's the story of Eliza Griswold's book. And in some ways, it's a book about idealism in general.

Idealism and the desire to do good are beautiful and inspiring instincts. But Circle of Hope seems to me to be an indictment of the lack of structure and protection and thought that came out of this religious movement in the seventies. Anti-institutionalism was institutionalized.

I understand and believe that institutions and structures and traditions, they need eruptions of innovation and radicalism. But 50 years on from the Jesus movement, there's so much damage that's happened because of the turning away from the lessons of history and tradition, and the turning away from structured ritual, and even a turning away from a certain bit of formality.

These things — tradition, liturgy, ritual, and formality — protect us from one another while also making space for meaningful encounter in that space where we enter into pursuit of the divine with others. The Jesus movement wanted radically authentic encounter and saw these more staid practices as nothing more than a hindrance.

And so one of the legacies of the Jesus movement and of much of non-denominational evangelicalism writ large is that encounter lost its guardrails. Personal relationships became overly familiar, leading to manipulation and spiritual abuse. In many cases, devotional practices such as group singing became overly emotional, leading to a religion that often neglects the intellect and fails to disciple its followers into truthful living.

Griswold's response to me when I shared these thought was: "You cannot transcend incarnation ... You can't sort of think or believe or pray your way beyond the limitations of the human world."

I also thought the book was an example of something I’ve lived, experienced and observed: placing far too much hope in what a local church can do and provide. It reminded me of my conversation with

actually, and her first book Orphaned Believers. In that book, she quotes Flannery O’Connor, who said that “to expect too much [of church] is to have a sentimental view of life and this is a softness that ends in bitterness. Charity is hard and endures.”But when church is sold to so many as the answer to all our problems and needs — spiritual, practical, relational, etc — it sets people up for failure. And it also places enormous pressure and far, far too much weight and expectation on the church leaders and pastors. How many pastors do you know who are expected to be too many things? The nondenominational, lower church model is attractive to narcissistic leaders but it chews up good people with functional consciences.

Griswold is a contributing writing for The New Yorker and directs the Program in Journalism at Princeton University. Her 2018 book Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America, won the Pulitzer Prize.