*** On June 20, 2024, Joel Searby was arrested in Florida’s Alachua County and charged with soliciting a 15-year old boy for “sexual acts,” according to multiple news articles which quoted from a police report. Searby has yet to stand trial. This information was surprising to me, to say the least. I have decided, for the time being, to leave this post up and append this note at the top. ***

Hello friends,

I cannot think of a better week to launch my new Builder Interview Series. While our national leaders are failing to lead, I'm talking today with a man who is trying to build something new.

In American politics, we saw the latest sign of total dysfunction in Congress, as House Speaker Kevin McCarthy was ousted for daring to pass a bipartisan solution last week to avoid a government shutdown.

Many people are desperate for a new kind of politics, and Joel Searby has dedicated the last several years of his life to that cause.

Joel — who is writing on Substack at

— worked on the Evan McMullin presidential campaign in 2016, and since then has been involved in numerous efforts to find a new middle way for the many Americans who are deeply frustrated with our politics.Most recently, Joel was executive director of The Forward Party, which is building state parties around the country to give people a way to build a movement from the ground up. Joel recently left that role and we talk about what he's up to now. He remains invested in and hopeful about the future of The Forward Party.

Here's a partial transcript of our conversation:

Jon Ward: For the last two years you were traveling the country, organizing local chapters of The Forward Party. Talk about how many places you went to, what you were doing, but most of all, talk about what you learned about the country during those travels.

Joel Searby: So the new Forward party launched in July of 2022, and the goal was and remains to build a new political party for America, and to give people a voice in their government. And that is a response to what you're referring to, Jon, that there is a real desire out there right now for something different. I think we may talk about that a little bit later, but I was all over the country helping to start our state parties because if you're starting a new national party, what that really means is you're starting a whole bunch of state parties, because every state has a different set of rules and challenges and complications. So for the first 21 weeks of the year, I was on the road 18 of those, in 18 different places, and that was largely meeting with our emerging executive committees. In each state where we're trying to get established, we needed to have an executive committee, a group of leaders who would carry the banner and do the work of building the party in their state and then pushing that down to county level and local level.

So I would go in and meet with these folks who had come into the Forward Party ecosystem, usually organically. Very few of them were politically experienced, which was a really interesting piece of what I found out there. But they came because they were hungry for something different and they were attracted through different means. Some of them were attracted to Andrew Yang and his vision for America, a former presidential candidate. Some came through former Republican governor Christie Whitman of New Jersey. Some came through David Jolly, former Republican congressman, who was kind of tip of the spear, Never Trumper, was part of one of the three organizations that merged. Some came through friends, who just told them about it and the launch was big enough that you had a couple hundred thousand people literally kind of influx into the system. And then people sign up to say, I want to help lead this thing. And so I would go in to meet with these folks and help them get their bearings and think about a strategy and how to build the party in their state. So that's kind of what I was doing.

Jon: What are your hopes and fears for all of that energy? It's pretty much a tale as old as time — people come into politics or any other venture with a lot of idealism, especially if they don't have that experience that you're referring to. Lots of optimism. Politics can grind that down pretty quickly. So what are your hopes and fears for all of that optimism and hopefulness?

Joel: Well, I'm already seeing I think two cycles in a year now of people being ground up and leaving, for a variety of reasons, and then new people coming in. And so my hopes and fears are grounded in reality and seeing it happen already in the Forward Party. And also I've been in politics 17 years, so I've seen this cycle time and time and time again that you're referring to. And the fear part is that really good people who have not just idealism, but good ideas, and have thoughtful ways forward, get pushed out because it's so frustrating and it's so calcified and new ideas are killed in the cradle in politics.

The hope that I have is that I have also seen people persevere who came in early with that idealism who have stuck with the concept and with the heart of what the mission is: to create this new way in our politics. And they have held tight to that dream, I guess, if you will, because they know it has to happen. The people that I'm thinking of, even as we're talking right now — a handful of the leaders who have just been so steadfast and not without their concerns or their frustrations, setbacks — but they just, they're like a dog on a bone. They just won't let go because they know, like I know, and this is what I sense when I'm out in the country, that people are just so hungry for something different. And the data really do support that. The people that are coming into the Forward leadership, at least, they're not motivated necessarily by the data. They're motivated by their own neighborhood, their own community. They go to barbecues and everybody's frustrated. Some people live in enclaves that are far left or far right, but most people don't live that way. Most people live in communities and neighborhoods [where] people are really frustrated. And this is the things that people are talking about at barbecues and cocktail hours and block parties and school sports.

Jon: What have you learned about what institutions can do? In your case it was the Forward Party, but I think this question applies to many institutions that are trying to build something sustainable, whether it's in politics or business or something else. What can institutions do to retain people to help them get over and past that sense of frustration and futility? Because that is a constant challenge. What can be done institutionally to build something that helps keep people moving forward?

Joel: I don't have a definitive answer, Jon, because I'm so steeped in this new politics movement that is really young in the scope of US history. It's about, I would call it about 15 years old. I've been in it for nine. But what I'm starting to see emerge is a community of people who know each other and support each other, not so much in any one institution. But the people who just keep sticking it out, keep talking to each other, and they keep innovating and they keep learning and they keep adjusting. And rather than being specifically tied to one solution, the people that are enduring that I'm seeing are the people who are staying flexible and recognizing that for a new way to emerge in our politics, it is going to take a whole bunch of different things. And when I think about what institutions can do, you can help to make that happen, to make those connections, those interpersonal connections, happen.

One of the things I'm concerned about for the Forward Party, or anybody else, is that you end up so focused on a singular mission. And this happens across the reform ecosystem as well. People who care about ranked choice voting, or fusion voting, or any number of specific reforms — they forget that they're part of something bigger, and that there is what I now do call a movement. I was hesitant to call it that until about the last six months. I do think it's now emerging into a new movement in American politics. But be that as it may, I think that creation of connections across disciplines is really, really important because it gives you perspective. I also think a really important part is just helping people understand history and having a long view. Anytime you're trying to make systemic change, you have to see it for that.

I've told people I think I got two good decades left in me ... I've got almost a decade in now to this new politics work. I'd like the whole next decade to be taking what I've learned, and starting to really put wins on the board, and moving the ball, so that the last decade of my productive life, I can maybe take some lessons that I've learned in 20 years and help to pass that onto the next generation. So I'm thinking in a three decade cycle, and I think the American political system doesn't like to think that way. It's not built to think that way. And that's one thing that I think institutions can do. One of the biggest challenges about that, though, is that takes long-term resource commitment, right? What organization has a 10 year financial runway? None. And so the concept of having enough resources to do that over the long haul is a real challenge.

Jon: So what did you learn about the country?

Joel: First and foremost I learned what I already knew, which is that there are an incredible number of really amazing people in this country, and it also is radically pluralistic. I was really pleasantly surprised working within the Forward Party. I think people had an assumption that they would be from a certain ideological perspective, but I kept going into these rooms and finding people from the progressive left and the conservative right and the middle all signing up to be leaders in the Forward Party. And also, even though the reform movement, writ large, has a real kind of white male bias problem in terms of its leadership, that was not necessarily the case in many of the places I was popping in with the Forward Party. And I was finding diversity, not only of thought, but of background. And that just reminded me that, yes, we're a radically pluralistic country and, yes, we have to have solutions that reflect that, but people from those backgrounds are showing up and they want to help find those solutions.

This group of people that are frustrated is, yes, it's very diverse, but there's a unified desire to make something different happen that I don't think has been tapped into really at all yet. We haven't seen a mass movement, which is why I think we're at the very front of what I would call a movement, but it's not a movement in the sense the civil rights movement was, because it hasn't grabbed a hold of a single message or shown mass action yet. And that's what I think is the next phase. That's what I'm looking for, and honestly, I'm going to try to help catalyze it in the next year or two.

Jon: That's really interesting. I remember there was a dinner that the Forward Party held for journalists and some other folks in DC that you invited me to last year. And one of the big points of feedback was that without a single message, essentially there's a limit to what something like the Forward Party can do. And I think at the time, and even probably now, a lot of people involved in the Forward Party are okay with that because they're trying to build at the local level. But I think when we talk about, 'What can an institution do to retain people despite their discouragement?', I do think that single message is probably part of that. What are your thoughts on what that message might be? How specific does it have to be? How issue oriented does it have to be? It's such a tricky, complicated and really hard to predict kind of thing, but you have probably thought a lot about this.

Joel: I've thought a lot about it, Jon ... I've studied movements a lot over the last five or six years. I've done a lot of research. I'm just finishing a book that's going to be published next year on movements. And one of the things that I've seen that's really important to remember is that any real movement — which is I define as a group of leaders who get together and advance something that brings lasting change — that movement has to include a bunch of different players. No single organization or institution or single person is the movement. It's always, over the course of history, an ecosystem of different players. And I'm heavily influenced, as I said by the civil rights movement.

When I look at the civil rights movement — which was really the last mass movement that really significantly altered the country in ways that were universal — there were all kinds of different groups. There was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, there was the NAACP, there were all the local groups that were sometimes chapters of those groups and sometimes their own little groups. There were pastors groups. You had a variety of types of leaders. You had influencers, you had artists like Harry Belafonte, you had all these different people engaged in this, and no single organization was the movement. So first and foremost, I think it's probably beyond the purview of any single organization or institution to get to say this is what the movement means. I think more likely it is going to emerge organically, and that's what will be a part of sparking mass action, which again, has not really taken place yet. You've got a hugely frustrated electorate right now. I think most people are sitting on the sidelines. I think what will emerge will probably have something to do with this concept that people's lives are being deeply impacted at the local level first, and then at the state level by partisan infighting, and this system that is just simply not working to actually solve real problems for people in their communities, which is what the government is supposed to do.

I think it's going to have something to do with people having a succinct way of not only expressing that frustration and anger, but then — as with any great movement — ... any great movement for good change also takes the anger and the frustration and the need for change and packages it up in a way that says, 'Here's the change we want to see and here's what we believe will pave a new way for the things we want to see in our country.' So I would be foolish to say, I think I know what that message is going to be. It's not my world, and I don't think that's how it's going to happen. I think it's going to emerge organically. I hope it happens in the next year or so because I think the conditions are really ripe for that to happen.

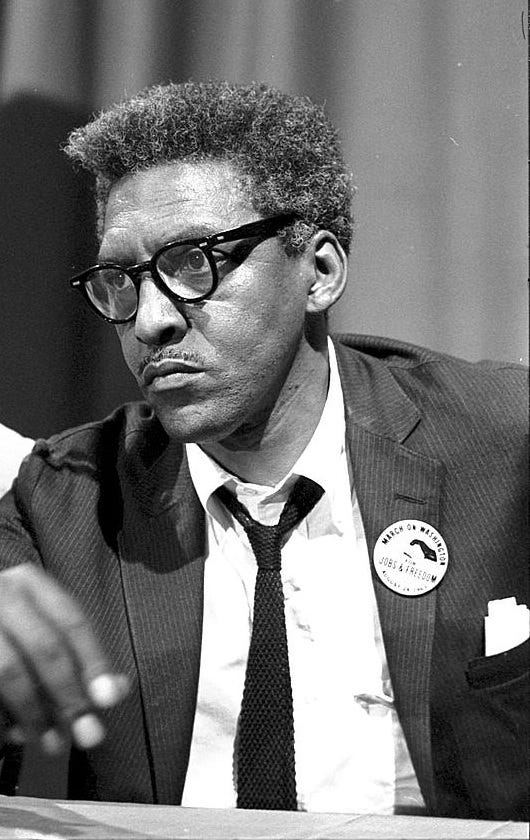

Jon: Have you studied at all Bayard Rustin, the civil rights leader who organized the [1963] March on Washington?

Joel: I have actually. One of my favorite civil rights books is called Bearing the Cross. It's really the definitive bio of Martin Luther King Jr., from the period of the initial Montgomery bus boycott to his death. And Bayard is a key figure throughout that whole story ... His role in that was really, really key. It's a good example of how one person had relationships with a couple of different organizations but drove toward a single mass action that ended up being a catalyst long term. It actually didn't get much done immediately. That's part of the story of the March on Washington that's not really told. It's like, some people thought it was a total failure. Pieces of it then got grabbed by the conscience of the public and helped to advance things later on, but not necessarily in that moment.

Jon: What drives you to keep working? What gives you fire in your belly?

Joel: For me, I've always been heavily motivated by my faith and the way that I've navigated that, especially this last couple years as everybody has been asking themselves, 'What does that even mean? What is my relationship to institutional faith and how do I think about faith?'

Whatever faith you may be, I think a lot of people through the pandemic and over the last few years have been wondering what that means. But for me, grinding that down to something that I can kind of hold onto and act out — irrespective of how I may feel about the institution of the Christian Church or how I even feel about the theology or the philosophy of specific parts of my faith — I really drive toward three things that have motivated me and I come back to quite often. One is the Lord's Prayer that most people are familiar with, specifically this concept of a relationship between heaven and earth.

I think the church totally missed this idea that the prayer says, as praying to the Father, God, your kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven. And often times faith of any type has been thinking about the long-term — call it heaven, call it the afterlife — that they forget there's actually a life right now. And that's very explicit in the Lord's prayer that Jesus gave us — 'on earth as in heaven' — right now. And so that's kind of a grounding thought for me: if I care about the world looking a certain way and having a certain set of characteristics and values in it, I need to care about how I live right now and how I interact with the world. So that helps me stay grounded and caring.

The second piece of this motivation for me is found in John 15. Jesus is talking about being the vine and his followers being branches and staying connected. And that has always been really important to me, to just kind of have a time every single day that I stay connected to something that matters. And I think that applies across faiths honestly, or even people of no faith. Just waking up in the morning saying, 'What am I connected to, and how is that giving me kind of a thread of purpose through my life and through my days?'

And then the third one for me is what are known as the fruits of the spirit, basically this set of traits for what it means to look like a follower of Jesus. Again, I think this applies to a lot of people because they're kind of universal traits of goodness. I'm looking for what is coming out of me every day and how am I applying these traits to my work and in politics. And so I look at that and I say, 'How am I bringing love and joy and peace and patience and kindness and goodness and gentleness and faithfulness and self-control into the world that I work in, which happens to be politics?'

And so those things kind of keep me going and I try to come back to them when I feel like I'm a little bit untethered and unmoored. They tend to give a framework.

Jon: I really liked the specificity of that. I appreciate the answer. I wanted to ask you about discouragement in your own life and moving past that. What helps you get back up and keep going?

Joel: Well, some days I wonder if I will. It can be pretty tough when you're in any kind of fight against a very entrenched way of thinking and doing things. And certainly trying to chart a new way in our politics is that.

Jon: And I should say it's not just politics. It's the world of money, in a world of what I think some people call post-capitalism, where there's very little restraint on the free market and on the strong trampling the weak.

Joel: Education is seeing it: higher ed, K through 12. We're seeing it in a lot of venues, just that grind, that frustration.

I would say I don't have a magic bullet for what keeps me going. I've always been someone who can't imagine not keeping going until I breathe my last. I'm fortunate in that way. I know others maybe have not felt that way when they hit their dark times. But I've always kind of been driven by this sense of, 'What else am I going to do but just keep trying to do my best to bring something good into the world?'

And on days when I can't, I'll just sit and look out the window, or work in my yard and hope that the next day is going to show up and it could be a little bit better. So there's a certain sense of just perseverance that just says, I'm just going to keep going.

And there is for me a belief that the work matters. [I'm] very influenced by a guy named Tim Keller who wrote a book called Every Good Endeavor , that really is kind of a modern theology of work. It embraces this concept that all types of work have value, and that just the doing of the work is inherently good. And so I take a lot of solace in the fact that I may not be able to pull any one lever and change the American political system, but that each little thing that I'm doing to try to build this new way, to try to bring these values into reality — and hopefully layering on one person and then another and then another who also share this concept that it can be different and that it has to be different — that's okay for me. That's enough.

I don't need to be the part of being on the TV every day or being a giant social media influencer. I just want to be faithful to the work every day.

The Five Top Stories of the Week

Are you busy? Are you avoiding the news because politics sucks? Yeah, lots of people are.

If you want a quick 10-minute read to catch up on what happened at the end of the week, so you can get on with your life and your weekend, I'm doing that each Friday. It's focused on substance rather than hype, with links to go deeper if you want.

You can read today’s version here. The top 5 stories worth remembering were:

Republicans get rid of their leader in the House of Representatives

U.S. assistance to Ukraine is in limbo

Trump is losing control of his New York real estate holdings

Biden administration constructs wall on portion of U.S.-Mexico border

Newest U.S. senator is sworn in and faces questions about whether she’ll seek to stay

Interesting Reads

Lessons for the Press in the Age of Trump by Jack Shafer for Politico

Talking to reporters who’ve worked with Baron does not help unlock the mystery of his success. They’ll tell you he’s a cipher but also a stickler for accuracy. That he always demands more reporting. That he’s an expert at developing a story — the best illustration of that talent being how he turned what could have been a story about errant Boston priests into a story about a corrupt global institution. Not every editor has the patience that Baron exhibited to capture smoke and turn it into fire the way Baron often did.

But it’s not enough to demand old-school journalistic values, or else great editors could be assembled from a cookbook. A great editor must find a way to become a presence in the minds of his reporters, a resident nudge pushing them to nail down facts and the courage to cut throats in the temple.

It might turn out that the Marty Baron secret is no secret at all and is as reproducible as the sunrise. In Collison of Power’s epilogue, Baron defends the so-called objective method of journalism against its growing number detractors. Practitioners of the objective method, he notes, don’t claim an “objective” point of view, nor do they give all points of view equal weight. It means, as he writes, that journalists should “never stop obsessing over how to get at the truth.” He continues, “we must be more impressed with what we don’t know than with what we know, or think we know. We should not start our work by imagining we have the answers; we need to seek them out. We must be generous listeners and eager learners. We should be fair.”

... As journalistic roadmaps go, Collison of Power will guide readers ably through the last stop in Baron’s career and detail the Post’s coverage of the Trump presidency. But its real service is the way it open-sources the Baron method on how to break consequential news: Obsess about getting the truth. Know your limits. Listen. Be fair. Report, report, report and report some more. Then do some more reporting.

Justice Kavanaugh taps the brakes on Supreme Court's sharp move to the right by David G. Savage for The Los Angeles Times

In June, with the fate of the Voting Rights Act in doubt, Kavanaugh cast a fifth vote to join Roberts and rule that Alabama's Republicans must draw a new congressional district that might elect a Black Democrat. They reaffirmed that position last month.

The four other conservatives joined a dissent by Thomas that would have barred considering the racial divide among the state's voters when deciding whether a redistricting plan is fair.

A year earlier, Kavanaugh cast a deciding fifth vote to uphold the Biden administration's plan to require a COVID-19 vaccine for millions of workers at hospitals and nursing homes that receive Medicare and Medicaid funds.

Twice Kavanaugh played a key role in upholding Biden's immigration policies against lawsuits brought by Texas Republicans.

Kavanaugh's emergence as the sometimes unpredictable middle vote did not surprise Washington attorney Lisa Blatt.

Blatt, who has argued more cases before the court than any other woman, drew sharp criticism for endorsing Kavanaugh's confirmation in 2018.

She said then she was a "liberal feminist" who had clerked for

and wished Ginsburg had "all nine votes." But with Republicans in control of the White House and the Senate, she said Kavanaugh was "the best choice ... in these circumstances."

Kavanaugh's "first five years are exactly what I thought they would be," she says now. Although disappointed that Kavanaugh and the court overturned the right to an abortion in the Dobbs case, she said his overall record "shows he's a mainstream conservative who is acutely aware of the practical consequences of the court's decisions.”

“I think this is Justice Kavanaugh’s court, meaning his vote will continue to have a decisive effect in the court’s most important cases."

How Gerontocracy Explains the Matt Gaetz Clown Show by Ross Douthat for The New York Times

Unfortunately now is when we actually need some kind of fiscal adjustment. Even if the inflation generated by Covid superspending and pandemic disruptions is gradually abating, higher interest rates have dramatically altered our spending trajectory. After a long period in which low interest rates enabled the government to borrow trillions without adding much in annual debt servicing, last week the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond reached 4.5 percent — threatening a future, according to the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl, in which debt payments cost roughly the equivalent of a second Defense Department every year.

That’s a future that is likely to starve any priority apart from shoring up entitlements. Industrial policy? Family policy? Military spending in a multipolar world? Forget about it: The money won’t be there. Populists, socialists, defense hawks — they all could use a Ryan-like figure now, or a Simpson-Bowles Commission, or a replay of the Barack Obama-John Boehner deficit negotiations that actually gets to a grand bargain.

What they have instead is Matt Gaetz. Who is, in his way, telling the truth when he criticizes the can-kicking style in which McCarthy has tried to negotiate between his own members and the Democrats, or when he tells the reporters gathered for his performances that the leaders of both parties are custodians of American decline. But Gaetz has, of course, no politically plausible vision of his own — neither a means of selling his own party’s voters on entitlement reform nor a willingness to strike a difficult bargain with Democrats even if such a thing were possible. He’s just using our fiscal crisis as a ladder; the worse the problems, the easier the climb.

John Kelly goes on the record to confirm several disturbing stories about Trump by Jake Tapper for CNN

“What can I add that has not already been said?” Kelly said, when asked if he wanted to weigh in on his former boss in light of recent comments made by other former Trump officials.

“A person that thinks those who defend their country in uniform —or are shot down or seriously wounded in combat, or spend years being tortured as POWs — are all ‘suckers’ because ‘there is nothing in it for them.’

“A person that did not want to be seen in the presence of military amputees because ‘it doesn’t look good for me.’ A person who … rants that our most precious heroes who gave their lives in America’s defense are ‘losers’ and wouldn’t visit their graves in France.

“A person who is not truthful regarding his position on the protection of unborn life, on women, on minorities, on evangelical Christians, on Jews, on working men and women,” Kelly continued.

“A person that has no idea what America stands for and has no idea what America is all about. A person who cavalierly suggests that a selfless warrior who has served his country for 40 years in peacetime and war should lose his life for treason – in expectation that someone will take action.

“A person who admires autocrats and murderous dictators. A person that has nothing but contempt for our democratic institutions, our Constitution, and the rule of law.

“There is nothing more that can be said,” Kelly concluded. “God help us.”