Hello friends,

I’m not saying, in the headline, that this was the intent of Star Wars. I am saying that there may be a lesson for us in comparing the Empire to real life.

Here’s what I mean: I thought of an image of a storm trooper while reading Andrew Whitehead's most recent book.

Artist Scot Erickson painted a storm trooper in the style of a religious icon. The soldier's white and black armored head is framed by a halo. His right hand is raised in the same way as Christ's is portrayed in one of the most famous iconographic paintings, Christ Pantocrator. And also like that painting, the storm trooper holds a large bound copy of the Scriptures under his left arm.

Above the stormtrooper's head, there is a word. Empire.

It is an ironic painting, but it is making a very serious point.

Imagine if George Lucas had written into the Star Wars script that Emperor Palpatine's message to his political supporters and his soldiers was that the Empire and the Christian faith were inseparable. Imagine how Luke Skywalker and the Rebel Alliance would have felt about that.

That's what America has done, this painting argues, and it's what American Christians continue to do when they say that the United States is a Christian nation.

Andrew Whitehead's book American Idolatry argues this as well. But Andrew also says that the Christian faith has fallen prey to aligning itself with political power, domination and empire going back to the early days of the faith, when Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and used it for his own political purposes.

Andrew is Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of the Association of Religion Data Archives (theARDA.com) at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at IUPUI, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Here’sAndrew’s Substack

His first book in 2020, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, with Samuel Perry, was a data-heavy sociological book that was, in their words, "the first comprehensive empirical analysis of Christian nationalism in the United States."

Andrew's new book is a more personal look at Christian nationalism. It's still written with the rigor of an academic, but it conveys Andrew's personal convictions about what the Christian faith teaches and asks of its adherents, and how Christian nationalism "betrays the gospel and threatens the church."

Andrew is a Christian who writes of his upbringing in small-town conservative America, going to church every week. And he says that when he learned the history of Emperor Constantine, he wondered "was it God's plan all along to win over the most powerful person in the world at that time to ... help Christianity flourish?" And he also wondered, "Why didn't Jesus use this same tactic and embrace imperial power?"

That is a good way to think about how Andrew frames this book: What Would Jesus Do? That of course became a cliche in the 1990's, but it remains a fairly simple way to distinguish between the kind of dogmatic faith that stresses proper belief and a faith practice focused more on imitating Christ's example.

Andrew's book covers a lot of ground, and we hit a lot of the high points here, and I also ask him to go into his own personal back story some.

One theme from this book that has stood out to me is how Andrew, drawing on his sociological research and data, stresses that a hallmark of Christian nationalism is the desire to clearly demarcate who is in, and who is out, and to work to gain power to help those who are in, and to fight against those who are out. Power, control, fear, a sense of threat, and violence are the fruit of the spirit of Christian nationalism.

White Christian nationalism, he writes, "creates disciples more concerned with who is 'in' and who is 'out,' who is 'right' and who should be silenced, than with welcoming and accepting all. Instead of breaking down all dividing walls of hostility, white Christian nationalism glories in building them up" (180). "It does not share power, it only wields it."

He contrasts that with the way of Christ: leveraging power to benefit the common good and the weak, often by sharing it or even giving it away, and being suspicious of the pursuit of political and state power.

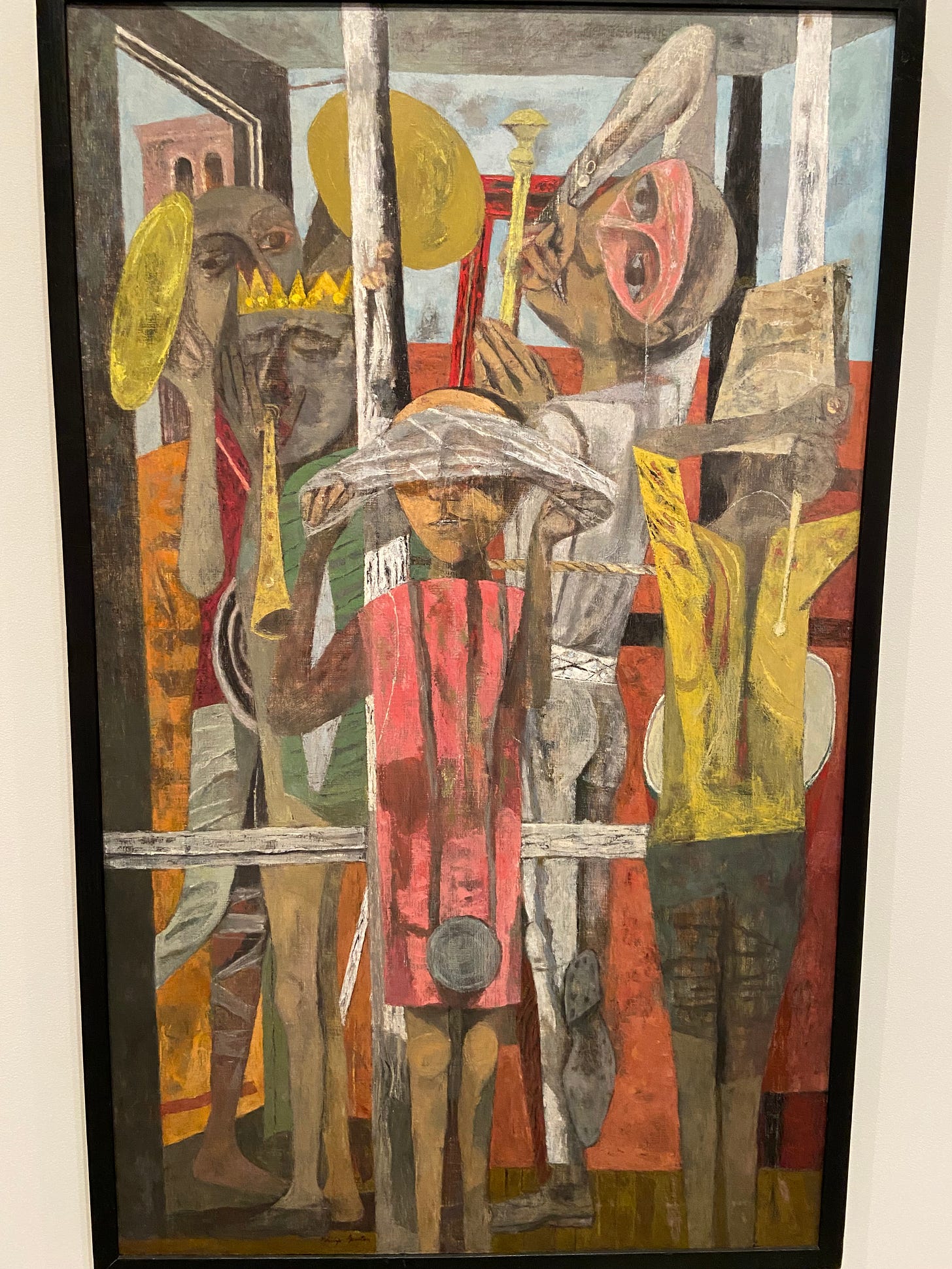

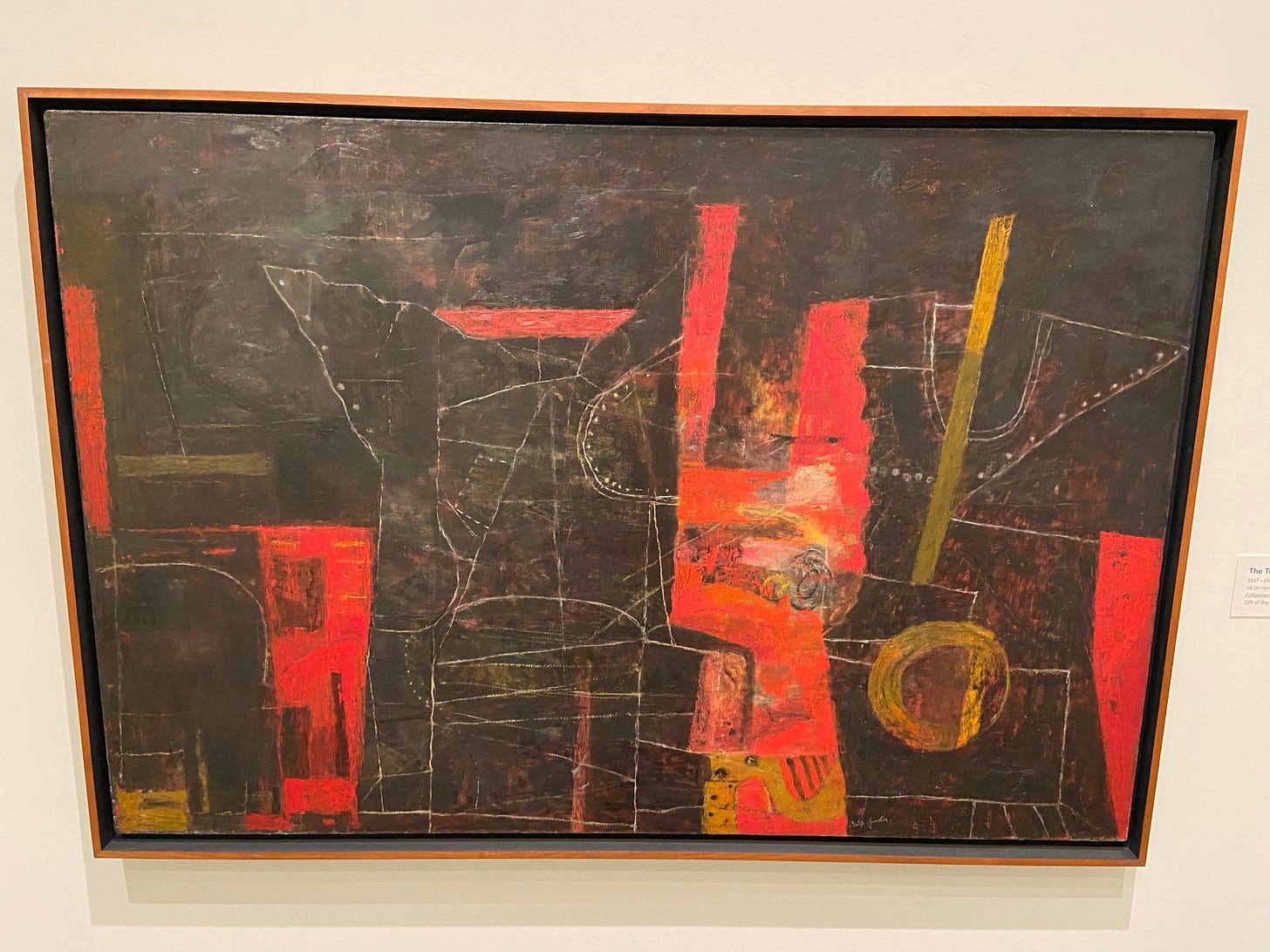

I can’t stop thinking about Philip Guston’s painting

Last weekend I was lucky to have the kind of experience that only comes along every so often. I walked into an art gallery and my mind was blown.

We walked into the National Gallery of Art two days before the end of a temporary exhibition of Philip Guston's paintings. I was able to trace his life journey from a teenage artist in the early 1930's to his period of abstract painting and through a period of almost total befuddlement at what to paint in his mid-50's. That was a painful liminal period that was necessary for him to enter his time of greatest production as an artist, for which he's best known.

There's just too much for me to try to say about Guston right now. I've purchased two books on him and would love to do a deep dive and come back with more organized thoughts.

But since that may never happen, here are a few scratched out thoughts on why I found the exhibit inspiring.

Guston was moved to respond to real world events, especially injustice and suffering, from his earliest days as an artist. And he pinpointed authoritarian forms of control and mob violence as one of his main targets for criticism. He came from a family of Eastern European Jews who had fled Ukraine to escape pogroms.

He never stopped evolving. He went through three main periods in his artistic career, but within and around each of those three periods there were many other stages and changes. He was political and polemical with many early paintings, and then went into an abstract period, and his late career saw him develop a totally unique style that lampooned characters of evil and malignance by depicting them cartoonishly.

He kept expanding. This has become a life theme of late, and keeps getting bigger for me.

I don't know if I've ever responded with such deep emotion to an artist. There is profound grief, anguish and even despair throughout his work. But I see in all of Philip Guston's paintings a defiance that is more beautiful than almost any I've seen. It is not a proud defiance, or even an angry one. It is not optimistic. It wonders where there is light, and if it has gone out. But it is a defiance that keeps looking for light, for beauty, for hope.

I was also deeply moved by his willingness to break himself and his art down to the most basic elements, to try to retain integrity in pursuit of what his art was seeking to express.

Here's how Brian Eno put it to Rick Rubin when discussing art, in a conversation where Guston came up (which is how I found it):

"What makes any work of art interesting, or gripping or effective is the feeling that somebody was living. Somebody was living it. Somebody was alert and alive and passionate in some way. And the way you get into that state is by being in unfamiliar territory I think. You're most alive when you're not quite sure what is going on, when you're slightly flying by the seat of your pants, and you have to negotiate it somehow. That's why we love improvisation so much, because people are deliberately putting themselves at risk in a way, soaring out into the unknown and somehow dealing with it. And that process of hearing someone dealing with it is the difference between life and death in a piece of work, I think, as opposed to a person who is just playing a thing they've done a thousand times before nad they don't sound like they're particularly interested in it. They just doing it right. They're not doing it well in particular. So I suppose all of the strategies and techniques that I use ... are really ways of trying to find myself in a new place, because I get excited when I'm in a new place. I like being in unfamiliar surroundings."

And one of Guston's most famous paintings illustrates another element of this authentic search for reality and truth: The Studio, 1969 shows an artist painting one of these white-hooded figures, vaguely reminiscent of a Ku Klux Klan member. But the artist himself is in one of these white hoods, smoking a cigarette. It is an unflinching statement: we are all complicit, in some ways, with injustice. The line between good and evil runs through every human heart. It is a commitment to look first at one's self before critiquing, and then after the critique to look again, and on and on that cycle goes.

By the way, Guston's paintings were temporarily stopped from going on exhibition back in 2020, because some people thought images of KKK members would be too upsetting to the public. Eventually, the museums made the right call and went forward with the exhibit, and thank God they did. I can't think of a better summation of the mindset that would try to bar the public from seeing Guston's paintings than the way that art critic Sebastian Smee put it in a Washington Post piece on the exhibit and the controversy surrounding it:

“I suppose all this is coming from a good place. But it’s in a bad place.”

Interesting Reads

Some good news

92,000 people attended a women’s volleyball match in Nebraska this week. That’s incredible! Every time I look at photos or videos of what happened in Lincoln, I get a little emotional. We have four daughters. I’ve just recently read two books that focused my attention anew on the revolting amount of chauvinism we are still dealing with in today’s society. This is a big statement about valuing and celebrating women in general.

America Is Using Up Its Groundwater Like There’s No Tomorrow by Mira Rojanasakul, Christopher Flavelle, Blacki Migliozzi and Eli Murray for The New York Times

Some bad news

“From an objective standpoint, this is a crisis,” said Warigia Bowman, a law professor and water expert at the University of Tulsa. “There will be parts of the U.S. that run out of drinking water.”

“We overpumped it,” said Farrin Watt, who has been farming in Wichita County for 23 years. “We didn’t know it was going to run out.”

American agriculture didn’t always rely on pulling huge volumes of water out of the ground. Until the middle of the last century, farmers were mostly limited to relying on rainfall or river water. Smaller wells were mainly just supplements.

But advances in pump technology after World War II created an American agricultural powerhouse, turning the west and the High Plains into a bounty of corn, alfalfa and other crops, delivering yields that surface water alone couldn’t support.

Last year the United States produced 39 percent of global sorghum exports, 32 percent of soybean exports, and 23 percent of corn exports, federal data show. America also exported more cotton than any other country.

That success has relied on pumping up more water than nature could put back.

As recently as the late 1990s, Wichita County farmers produced 165 to 175 bushels of corn per acre, well above the national average. But it came at a cost, requiring farmers to drain the aquifer in order to irrigate their crops. The area gets less than 20 inches of rain a year, on average, about one-third less than the continental United States as a whole — not nearly enough to replace the water being pumped from the ground.

Are We Ready to Talk About This Election Year? by

A tough question

I do not believe that unity is uniformity. In fact, I believe, now more than ever, that uniformity is dangerous and our attempts to convince everyone that our way is best and their way is worst, is only going to produce weaker and weaker generations to come. We will only grow stronger and more resilient in every way when we embrace diversity, welcome the nutrients we get from the other, and freely give our own resources.

I’ve been quoting Andy Crouch’s “flourishing is being magnificently oneself” for the past few years now because I believe, now more than ever, that this coming election year is an opportunity for us to magnificently hold to our convictions without malevolently othering the ones who disagree. The ones I know who do this well are the ones who, surprisingly, are the most welcoming to others and hearing other points of views on various issues. They’re also the ones who rise up in a forest full of spindly trees, growing strong and resolute, rooted not in their individuality, but in their interdependence on those around them. To be “magnificently oneself” actually means to be “magnificently malleable,” and I find that incredibly beautiful and compelling.

Censorship or free speech? Supreme Court likely to decide on 'momentous' question by Jon Ward for Yahoo News

Despite its conservative majority, the Supreme Court could find that social media companies have free speech rights too. If so, it would rule that when the platforms restrict, fact-check or take down content, this is constitutionally protected speech and the government cannot interfere, which is the view of many legal experts.

social media companies can — and, under the First Amendment, must — decide for themselves what their rules are and how to enforce them, conservative attorney Paul Clement argued for the companies.

“Just as the government cannot compel a newspaper to run content, it cannot ... compel a private parade organizer to include a group whose values it does not share,” Clement wrote in a brief to the Supreme Court.

“Those principles equally apply to a private social media company’s editorial judgment about what content to disseminate (or not to disseminate) via its website, applications, and online services.”

A Golden Age for Assholes by Sam Harris

"All information is in the process of being macerated by billions of tiny mouths and then spit back again and lapped up by others. So what is in fact mostly digital vomit at this point is being spread everywhere and being celebrated as some new form of nutrition. So there are people who we probably shouldn't know about, but do, and there are people who probably should have no any influence at all, but their influence is enormous. One of these people is Andrew Tate. And another is Donald Trump ... Both of these men are assholes."

"To be an asshole is to care about the wrong things. It is to not have one's priorities straight ... Of course many of us don't have our priorities quite straight, but only an asshole is inclined to celebrate this failure in public. To be an asshole is to mistake one's vices for virtues. It is to fundamentally misunderstand what it means to live a good life, and to encourage this misunderstanding in others. It's to mistake shamelessness for integrity, and a furious self-absorption for strength. An asshole is not just someone who lacks civility or tact. in fact assholes can be superficially charming, and probably must be to succeed. The problem is never just on the surface, whatever can be seen there. It's at the core."

"The problem with assholes is that though they might occasionally appear to care about other things and other people, they only truly care about themselves. Whatever causes they attach to just inflate the self. Whatever love they express is instrumental. Of course we are all assholes some of the time. We all have our moments of pettiness, and vanity and duplicity and callousness. But the task of living an examined life is to notice these moral failures as failures, and to transcend their logic. The purpose of becoming a student of human wisdom and an honest observer of one's own mind is to become less of an asshole more of the time."

So I'm reserving the term asshole for the type of person who simply doesn't care that this project exists: the committed asshole. The unrepentant one. The one who wears his lack of wisdom like a crown ...

Have a great Labor Day weekend!

Share this post