Hello friends,

I have these three things in common with Tim Alberta.

We both grew up as the sons of pastors in evangelical churches.

We both became journalists and have spent two decades reporting on American politics.

We both wrote books this year that are critical of the evangelical culture that we were raised in.

But in the year that I published my book, I did not write a magazine profile of the new CEO of CNN that was so deeply reported and revealing that the CEO resigned within days. Tim did do that.

But here's what both our books have done: we have challenged our upbringing with our upbringing.

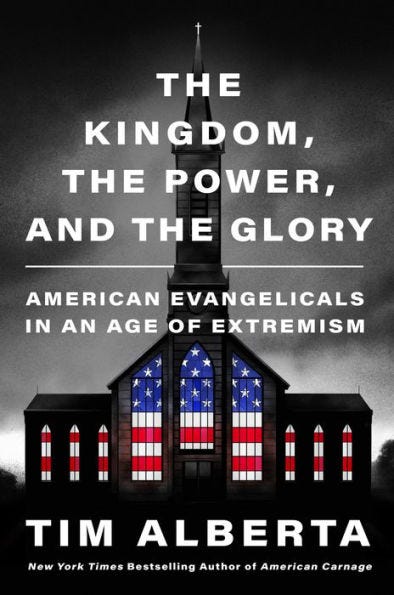

That's a paraphrase of a quote from an English professor named Nick Olson who is interviewed by Tim for his new book: The Kingdom, The Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals In An Age of Extremism, which will be available for sale next Tuesday.

On page 86 of Tim's book, Olson — who taught at Liberty University, ground zero for decades of the marriage of conservative Christianity and Republican politics — reflects on the many portions of the gospels where Jesus talks about how "a man should leave his father and mother" (Matthew 10:34-39; Matthew 12:46-50 / Mark 3:31-35 / Luke 8:19-21; Mark 10:28-31; Luke 12:45-53; Luke 14:25-33; John 19:25-27).

"It wasn't just about getting married and starting a new family," Olson said. "It was an instruction, I think, to challenge the things you're taught in your upbringing — with the things you're taught in your upbringing."

Whether or not Olson's exegesis is correct, he describes what both Alberta and I have done in our books. We have not rejected Christianity and we are not hurling insults at Christians. But we are looking at what we were taught growing up and comparing to what is being done in the name of Christ in America, and we are simply saying, "These two things don't match."

Tim and I are not alone. We are simply among the many of you who read this Substack and many other writers who are processing the apocalypse — the revealing — of the last decade. But I also know that for many of you, like it was for Tim and I, the comparing and contrasting of what we were being taught with what was being lived out in our churches, and in "Christian culture," began at a young age.

What I think our experience in political journalism gives us is access to a few things. We have learned the ways of power up close, by talking to, interacting with, and holding accountable people at all levels of political office all the way up to the presidency. We understand politics the way an NFL defensive coordinator gets football. The NFL coach sits in the skybox on Sunday, watching the game from way up high. Because of his thousands of hours of experience, he can see what is going to happen before most people do, and he is already thinking about the next play and the ones beyond that. Good journalists who cover politics can see politics the same way, anticipating — not with certainty but with a good base of knowledge and experience — how something done today leads to a certain outcome tomorrow or next year.

Neither of us are bona fide historians but we understand political history to a certain degree. And we have the ability to talk to experts on history, on politics, on government, and a range of other matters. We talk to them for public consumption. We talk to them privately. And then we take our findings to the public.

Here are some findings from Tim's book that I want to highlight. He traveled to churches across the country, and the breadth of his reporting is impressive. He interviewed some of the most well-known right-wing evangelical leaders who have preached the gospel of Trumpism: Robert Jeffress, Ralph Reed, Greg Locke, Jerry Falwell Jr., and others. (Now that I think of it there was no mention of the New Apostolic Reformation, which is too bad, because I would have loved to see where Tim's reporting took him there. But you can catch up on the NAR here).

You probably could argue that Locke is at least NAR-adjacent. He's of that milieu. And Tim's reporting finds that since January 6, 2021, American evangelicals who bought into the lies about the 2020 election and supported efforts to overturn the result have not used that moment as an opportunity to soberly assess where they might have gone wrong. They have not acknowledged that they believed and promoted falsehood after falsehood, and instead have endlessly turned to the next theory for how they are right. Instead of repenting, many American Christians and their churches have gone further into a deep sickness of the mind and soul.

"In the year after Trump left office, there was one demographic group most likely to believe that the election had been stolen, that vaccines were dangerous, that globalists were controlling the U.S. population, that liberal celebrities were feasting on the blood of infants, that resorting to violence might be necessary to save the country: white evangelicals," Alberta writes on page 302.

There is an alarming amount of radicalization in these churches, and increasing openness to and discussion of violence.

"The next January 6 should be open carry," said John Zmirak, a sidekick of Eric Metaxas. Zmirak actually said this while sitting next to Metaxas, at an appearance inside a church in Washington state on January 29, 2023. Alberta writes of that January 29 event that Zmirak also "repeatedly offered casual calls to violence, at one point citing the Islamic fundamentalist takeovers of Middle Eastern societies as a model for how Christians 'can take this one back'" (320).

Metaxas did not repeat his previous calls from December 2020 to "to fight to the death, to the last drop of blood," but he and Zmirak have said that those who have been found guilty of crimes by the U.S. justice system for their actions on January 6 are like the founding fathers of America who fought the Revolutionary War. Metaxas, who lamented the demonization of opponents when I last talked to him in 2018, routinely compares Democrats to Nazis (Vladimir Putin likes to tell the Russian people that there are Nazis in Ukraine and that's why they've invaded that free country).

Chapter 12 of Tim's book is a sobering look at the results in history when a religious movement morphs into a political movement, and allows its identity to be taken over by political imperatives and goals. He does so through the eyes of Cyril Hovorun, formerly one of the top officials in Russia's Orthodox Church, which has been coopted into Putin's mixture of politics and religion, and through the eyes of Miroslav Volf, a theologian who grew up in the former nation of Yugoslavia, who watched the Balkans descend into bloody civil war and genocide after years of "religiously motivated reassertion of ethnic identities" (236).

Putin has baptized actions and policies that "might otherwise prove popular" by getting the Orthodox church to "create a spiritual rationale" for them, Alberta writes. When former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic delivered an address to his nation that "sparked the civil war," in which he "cited the recorded persecution of his people by rival religious factions," "he delivered the message flanked by Orthodox priests" (236).

In 2016, Hovorun submitted an essay to First Things magazine "arguing that Trumpism could become America's first political religion." But, "the article was rejected."

But, Volf noted, "the best antidote to bad religion ... is good religion" (244).

This is tricky territory, ever setting one's self or side up as "good" against others who are "bad." I reject those labels when it comes to me and those I disagree with. But we do need to seek to make value judgments about which courses of action are better than others, and how to walk more in the good ways than in the bad. The trick is to separate good ways from bad ways while also recognizing that all of us are a mixture — inside ourselves — of many different elements that fluctuate between health, nobility, flourishing and decay, malevolence and corruption.

The question of identity is crucial here. I concluded in the wake of 2016 that the reason I saw loved ones going along with Trumpism was that their political identities had directed their decisions much more than their spiritual identities. Volf makes a similar point that, as Alberta puts it, many "Christians are claiming to navigate ... via religious identity but are actually navigating … via political identity" (238).

When I was 24 or so, I came to the end of myself in some ways as I burned out on a fanatical pursuit of the evangelical faith I had been raised in. I write about this period in Testimony in some detail. But I didn't turn away from Christianity. Instead I stripped my faith down to its roots, its bare essentials, and I did the same to my identity. Who am I, really? I asked myself. At the end of the day. I needed to answer that to keep going, to get out of bed. The answer came from Galatians 2:20, after many days of reflection: "I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. The life I now live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me." I resolved not to find my core identity in work achievements, or others’ opinion of me, or money, or even family.

Rachel Denhollander, the attorney and advocate who has struck fear in the hearts of sexual abusers and those who soft pedal or hide their crimes, also talks about this with Alberta. "Define your identity," she says. "If you do that, you will be able to stand up against abuses of your theology and speak out against your own community. You will be okay with not having a home, with not fitting in anywhere, because your identity is not tied to anything here."

"When you lose sight of your identity," she added, "it's easy to lust after power, and to justify the moral compromises necessary to achieve it" (397).

Alberta said this in our conversation: "What's clear to me is that inside the American evangelical movement, far too many believers have begun to view their faith through the prism of their national identity rather than viewing their national identity through the lens of their faith ... think that's really the crisis at hand that I've tried to address here.”

You see this merging of "Christian" identity with right-wing politics, and even with Trump himself, most clearly in the New Apostolic Reformation sphere, where believers increasingly speak of Democrats and liberals as controlled by demons, or even as literal demons. "People like Nancy Pelosi, she’s a demon," said Michael Flynn, Trump's former national security adviser who has been at the head of merging Qanon conspiracism with evangelical church rallies across the country (you should watch the Frontline special on Flynn if you haven't seen it). Former Nixon dirty tricks master Roger Stone, of course, has joined forces with Flynn. And if you need evidence that Stone knows an easy mark when he sees one, here's a piece I wrote about how Stone is using apocalyptic religious rhetoric and hanging out with charismatic Christians, while also talking about demonic possession of the Biden White House.

But Alberta's book documents that Christian Trumpism and demonization of anyone who disagrees has spread beyond those places, aided and abetted by conflict profiteers who have made "fear and hatred a growth strategy" inside the evangelical subculture for decades. He cites Charlie Kirk as a prime example of this.

Volf warns that if "political religion" is to be stopped, and the potentially calamitous mistakes and horrors of history are to be avoided, the church must remember that "it must be 'an unreliable ally' to every social, political, and government order of this world" (245). That was the advice of Karl Barth, the "Swiss theologian who prosecuted the theological case against Hitler and Nazism."

Alberta claims that, to his surprise, he found evidence that the doomsday industrial complex perpetuated by the likes of Kirk and Metaxas has been "floundering" more recently and that "somewhere along the line their momentum had stalled."

Alberta details the way that Russell Moore, Curtis Chang, David and Nancy French and others have begun to try to unite, connect and organize the many disparate and isolated members of the American church who do not worship a political leader or give blind allegiance to a political party. To this end, they’ve formed something called The After Party. And he quotes Moore voicing some, again, surprising optimism about recent developments.

"Obviously we still have enormous challenges. But one of those challenges is not an organized Christian nationalist movement gaining the power, at a grassroots level, to hijack institutions. That has now shown itself to be the case over and over again, whether in denominations or campus ministries or colleges themselves. Those institutions that are doing the work of church-based evangelicalism have not fallen to this nationalist political movement, and they don't appear to be in danger of falling," (349) Moore tells Alberta.

"There was an almost-universal sense in many of those institutions, not long ago, that this populist Christian nationalist takeover had an appearance of inevitability. And that has proven not to be the case. It's a surprise -- a very pleasant surprise," Moore said.

Time will tell if this is accurate and durable. But Alberta's book is a remarkable work of journalism, and I haven't even really touched on the way that Tim tells his own story of loss, heartbreak, and trying to come to grips with the moment in which we find ourselves. You can listen to my full conversation with Tim here on Substack or on your favorite podcast platform, at The Long Game.

P.S. I asked Tim what he would have told his 21-year old self about the Bible. Here's what I would tell my 21-year old self: 1) everyone’s version of what Christianity is is an interpretation, and nobody has the secret codes 2) look at the way the Bible has been read and interpreted over the scope of two thousand years, and 3) if the Bible seems to contradict what I can see in front of my eyes, don’t dismiss that but realize that created reality is God’s revelation as well.

I am planning to send a separate note with reflections on Rosalynn Carter’s memorial service, on a note by Cal Newport about online community and the death of Twitter, and interesting reads, since this has already gone quite long.

Thanks for reading!