hello friends,

I've interviewed

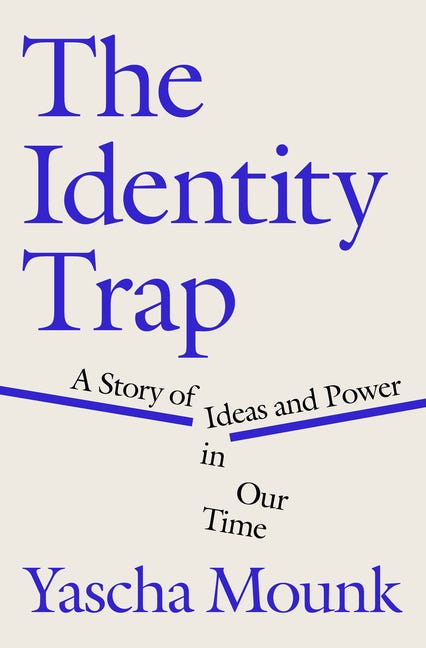

about his book The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time, which was released this week."Mounk has told the story of the Great Awokening better than any other writer who has attempted to make sense of it," The Washington Post wrote in a review.

Mounk chronicles the rise of a set of progressive political ideas “centrally concerned with the role that identity categories like race, gender, and sexual orientation play in the world.” He argues that advocates of this ideology fixate on identity to the exclusion of all else, rejecting “universal values and neutral rules like free speech and equal opportunity as mere distractions.” This “synthesis” has, Mounk writes, become very influential because of the way it took over cultural institutions, even as it convinced only a small number of people.

In a New York Times review of the book, Sam Tanenhaus describes Mounk as "a genuine master of ideological niche marketing." That's not a compliment, in case you were wondering.

Below is a partial transcript of my conversation with Mounk. You can listen to the full interview here on the Substack podcast app. I am releasing the podcast on Apple podcasts, Stitcher and most other platforms 24 hours after it goes live on Substack.

Yascha Mounk is the author of five books. He is a professor of International Affairs at Johns Hopkins University, a contributing Editor at The Atlantic, a Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and a Moynihan Public Fellow at City College. He is the Founder of

an online magazine that he launched in the summer of 2020, which publishes on .Mounk wrote this week about Persuasion's mission. It is, he said, "responding forcefully to authoritarian extremes on the right and to a simplistic understanding of identity on the left. But we’re also committed to offering a viable alternative, sketching the contours of what a positive vision of liberalism for the 21st century can offer."

Yascha's book says that we can reach across our differences and understand one another, and that we need to make the effort to do so, through conversation, debate, and relationship. I was not aware of the degree to which some progressive writers and intellectuals have argued that such mutual understanding is not even possible, and so they have discouraged the pursuit.

It's hard for me to imagine a world in which we do not at least try to understand and appreciate one another, even those with whom we have profound differences. That effort is at the heart of a free and prosperous society, in my mind.

Here's my conversation with Yascha Mounk, author of The Identity Trap.

Jon Ward: You write about being nervous about making some of these arguments and you also write about your response internally in your own mind and in your own soul to that feeling, which I think you actually name as shame. Can you talk a little bit about that and where you are in that process and why that has been something that has been on your mind?

Yascha Mounk: I've just been very struck over the course of the last five or six years by how frequently people I talk to, some who were ordinary people and some who had a very high profile, would make some very innocuous point and then say, ‘But of course I would never say this publicly,’ nearly as a kind of throwaway line. And I think that that is deeply unhelpful. It's unhelpful to them and it's unhelpful to our society.

It's one of the things that I think is driving mistrust in our institutions: that people can smell that people say something different on TV, and they say something different when they're in their own four walls. Now, part of the concern about this is that sometimes when people do say the “wrong thing,” there are these outsized consequences for that, and I'm concerned about that. But my book is not a book about “cancel culture.” That's not the main thing because, actually, as people starting with John Stewart Mill recognized and pointed out, the biggest loss is not from the person who says something and has been punished. It's from the person who chooses not to say anything in the first place, who chooses to remain silent.

The ambition of The Identity Trap, the ambition of my new book, is to allow people who feel torn to consider these ideas in a fair way, and to allow those who are concerned about the new set of ideas about race and gender and sexual orientation -- that have become so powerful over the course of the last decade – to make the most good faith, energetic, persuasive argument against these ideas.

Ward: There was a huge racial reckoning in 2020 and then a lot of backlash since then. Some people would interpret your arguments now as part of that backlash … I'm not even saying that it is part of the backlash, but they might say you're aiding and abetting the backlash. How do you think about that criticism or that response?

Mounk: I’m … a democracy crisis hipster. I worried about the stability of our democratic institutions before it was cool, but from the beginning I also was critical and skeptical of some of these new ideas on the left: the part of the political spectrum that I come from.

In my book called The People versus Democracy — which was all about explaining the rise of authoritarian populists like Donald Trump and showing why they're so dangerous to our democratic institutions — I also had pages about why it is so foolish for the left to give up on one of its grand traditional values, namely free speech.

I don't think I've changed my mind. I remain concerned about many of these ideas on the left today, and I remain very concerned about the fact that Donald Trump is running head to head in polls for 2024 and may be able to come back to the White House.

Ward: What happens to our political system in the US if [Trump] is able to get reelected and back into power in the White House, in your view?

Mounk: I was very worried the first time he was elected. It was four difficult years, but American Democratic institutions just about survived those. I think that should make us give us hope that we might be able to resist his concentration of power next time as well. But I worry that he is going to be more dangerous a second time round because he will — from the start – want to destroy independent institutions in a way he didn't in 2016.

He now has full control over the Republican party in a way he did not at the time, and he has a big bench, a deep bench of loyalists who've actually had four years of experience in executive office in a way that he did not the first time around. And he is much more bitter, much more out for personal revenge. In 2016, he had a vision for America — not a vision that I shared or found to be appealing — but I do think he actually in his mind was trying to do something for the country: make America great again. Today it's all about making Trump great again. It's all about Trump taking revenge. And so I would be very concerned.

I get why people might say this is the biggest threat, so why care about anything else? I think that's a mistake. One of the things that have allowed some of these more misguided ideas on the left to gain such institutional power after 2016 was Donald Trump's victory, which made it very hard to criticize ideas within progressive institutions, because you might be seen as running interference for Trump. But on the other hand, one of the things that explains why Trump is continuing to run neck to neck in polls with Joe Biden, for example, is that these ideas have come to have such a hold over our institutions, and that a lot of people therefore mistrust those institutions.

The best-case scenario is that Trump turns out to be ineffectual, that people finally get a message of how destructive he is and that we come out on the other end of that presidency with two American political parties that may be far apart ideologically — which is perfectly fine — which are both recommitted to the basic values, American democracy. The worst case scenario is that he, in one way or another, succeeds in what he started in 2020, which is to entrench himself in power in such a way that he can't be removed from office by democratic means, or that a successor can't be removed from office by democratic means. I don't think that would get us to the world of a straight out dictatorship, but it would put us in the company of countries like Turkey or Hungary, or others in which the main determinant of who's going to win the election is who has been able to reshape the rules of the games to their advantage. And that would be a very, very, very serious cost for our democratic institutions.

Ward: You called the ideas that you're critiquing the identity synthesis … You also talk about institutional guidelines for how different institutions, whether governmental or non, can deal with what you say is going to be a decades long debate … I'm curious whether you think that American political culture and debate and discourse has grown in thinking about things from an institutional point of view or not.

Mounk: I think the identity synthesis is a substantive new ideology, but has been shaped over the course of decades and which then became very influential in a very rapid manner. And so it'll take us a while to sort this out, in the same way in which various contestation between liberalism and Marxism — for a lot of a second half of the 20th century — in universities and other kinds of institutions. And so what I hope to provide with The Identity Trap, with this new book, is a primer that'll make people smarter about this, but actually explains where these ideas come from, what stands at the core, how they're being applied, and then supplies them with the best, the smartest, the most good faith arguments against these ideas, so that they're equipped for this fight that is going to continue for the next two decades.

The norms and practices that were inspired by the popularized version of them have been kryptonite for institutions. There's all of these very powerful accounts from people like Morris Mitchell, the head of a Working Families Party, a long-term organizer, and the Movement for Black Lives, of just how hard they have made it for progressive institutions with important missions to do their work. And so one of the things that I also want to do with this book is to give people a little bit of practical advice for how to speak up, how not to be the person that the lunch who says, ‘Of course, I would never say this publicly.’

Ward: I think one of the audiences for your book is going to be people who may have a negative reaction to some of the excesses of the identity synthesis or what they might call wokeness and who might be tempted to overreact, and I think your book is probably going to be a helpful tool to redirect some of that energy into a more constructive type of political engagement that still advocates for racial justice and the equality rather than having people swing from left to right as we've seen.

Mounk: I recognize that a lot of the people who are lambasting these ideas are reactionists who to turn people who share those concerns into reactionaries. And so I lay out that the best way to avoid that is to argue on the basis of substantive principles. Now, my own principles are that of a philosophical liberal who's, broadly speaking, on the center left, of somebody who cares about political equality and individual freedom and collective self-determination. Other people may be Marxists or there may be evangelical Christians, or there may be Buddhists or there may be conservatives. What's important is that you get out of this knee jerk space where you're saying, ‘I'll say the opposite of whatever my enemies are saying,’ and ‘If something is somehow woke or if some woke person says something, I'll say the opposite.’ That's not the way to argue in a substantial way for the vision of a better society.

I'm a full up anti-racist, a paid up crusader against these injustices. The problem with these ideas is that they're going in the wrong direction, that they're giving up on the proudest tradition in American politics. So they explicitly disagree with figures like Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King. And I think once you've understood that you can reclaim those values — in a way that will allow you to disagree with some of these progressive movements today — but which will naturally also make sure that you keep a very, very big distance from the true reactionaries, who want to exploit the excesses of these ideas… for their own political course.

Top 5 Politics Stories of the Week

If you don’t have time to follow the news most days, you can read this and get caught up pretty quick.

There’s a lot of noise and junk out there. The goal of this is to help you forget all the junk, and remember what mattered:

The Top 5 Stories were:

Leading Republican candidate for president insinuates that America’s top general should be put to death

Republican infighting sends U.S. government toward shutdown

Second GOP debate marred by bickering

Biden and Trump both curry favor with auto-workers during strike

Republican witnesses at first impeachment hearing say there’s no evidence for impeachment

Read more on each here.

Interesting Reads

I found Lore Wilbert's essay — in which she says the demise of social media is really a beautiful escape for us writers — really quite encouraging. Twitter's death spiral is a big reason why I'm doing the Media Diet Q&A on Monday's now.

I also experienced profound relief and even happiness when I read Lore's following sentence: "Social media was not made for serious writers and it will never work for us in the ways we’ve been told it would."

What Substack is doing right now is aggressively removing the need for some authors in particular to stay on social media. Some authors will stay because it’s their brand, it’s how they built their audience (i.e., they like to spar on Twitter, engage community on Facebook, post aesthetic work on Instagram, etc.) and how they will retain their audience. But for writers and authors who really have made a career out of writing, I think social media is losing the battle for their attention. People read those writers for their writing, even if they like getting a glimpse of their lives through Instagram or a taste of their accessibility through Twitter. By opting out of social media (all at once, or slowly, as I’ve been doing), we’re telling our readers, “Hey, I’m not an influencer or debater or celebrity or whatever. I’m a writer. I’ve always been that—even if I felt like I needed to jump through those hoops for a while there. It’s not working for me anymore and it’s not (really) working for you, even if you can’t see that yet. Instead, I’ll be over here, writing.”

Social media was not made for serious writers and it will never work for us in the ways we’ve been told it would.

Listen, it’s slow work. I’m not promising you any quick results. I’m promising you anti-quick results. I’m also promising you it’s work. You will have to show up, you will have to prove your ability to write, you will have to face yourself if you turn out to not actually like writing more than captions or tweets (and that’s okay!), you will have to acknowledge after some point in time that if no one is showing up to read what you write that perhaps you are not called to write (this one is a hard one to face), but if you are a gifted writer who works hard and keeps at it over a long period of time, you will look behind you and be surprised at the faces of men and women who are showing up to read what you write. You will have built an anti-platform, but a loyal community of readers—which is what we want anyway.

Americans Finally Start to Feel the Sting From the Fed’s Rate Hikes by Rachel Louise Ensign for The Wall Street Journal

Fed officials signaled last week that they plan to keep interest rates high for quite a while. For families who don’t need to borrow, higher rates might not affect daily life too much. But for those who do, the Fed’s aggressive rate increases are really beginning to sting. “The bite is starting now,” said Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab.

Borrowers shopping for mortgages or auto loans are experiencing sticker shock. New 30-year fixed-rate mortgages today carry rates around 7%, up from 3% two years ago. That increase can mean a home buyer has to pay hundreds of dollars more a month compared with two years ago. Rates on car loans have also shot higher.

Buying a home or car right now is “completely unaffordable for the typical American household because you’re mixing the higher borrowing costs with the high prices,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.·

A Ghost, Reborn: Wilco Pushes Forward On Weird, Beautiful ‘Cousin’ by Jonathan Cohen for Spin

On “Pittsburgh,” which Wilco unsuccessfully attempted to record for 2019’s Ode to Joy, the narrator casually reveals, “I’ve always been afraid to sing / somehow that’s all I do, strange as that seems / I’ve outlived my dreams,” and there are further existential ruminations on “Levee,” which boasts nakedly honest lines such as “I love to take my meds / like my doctor said / but I wonder / if I shouldn’t instead.” The disconnect between sound and vision is most striking on “Ten Dead,” where he matter-of-factly relays a news report of yet another mass shooting before deciding to go right back to bed.

“We all walk around tolerating this intolerable situation,” he says of America’s gun violence epidemic, which hit home in 2019 when his family’s house was sprayed with multiple gunshots from an unknown shooter in the middle of the night, in an apparently random incident. “It just becomes a part of our daily background atmosphere that we live with these things that are absolutely insane to live with. The sane response is to go crazy [Laughs]. It would be to go fucking nuts and go on a hunger strike or something, but most of us choose an insane reaction, which is, well, can’t do anything about it. Nothing’s ever gonna change, you know? To be completely blunt, that’s the equation we’re all sort of willing to make without discussing it that way.”

“But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t really fucking affect you,” he continues. “It does. It hurts to feel that ineffectual.1 It hurts to be in a society that fosters a dissociative state as a way to cope. That’s kind of what a lot of the record seems to be about to me, without maybe explicitly putting it there. There’s a certain detachment from the surroundings. If I look at the singer as the personality or the person, they don’t always seem to be relating to the environment of the music.”

Trump Floats the Idea of Executing Joint Chiefs Chairman Milley by Brian Klaas for The Atlantic.

“Trump is “openly fomenting political violence while explicitly endorsing authoritarian strategies should he return to power. That is the story of the 2024 election. Everything else is just window dressing.”

Wilco has a new album out today! I’ll be listening all weekend. See you next week!

Emphasis added by me, because this gets at something I was writing about this week in “Don’t Give up on America”: the way so many people feel powerless in the face of our problems.